Clik here to view.

Laura Ancona | Student Life

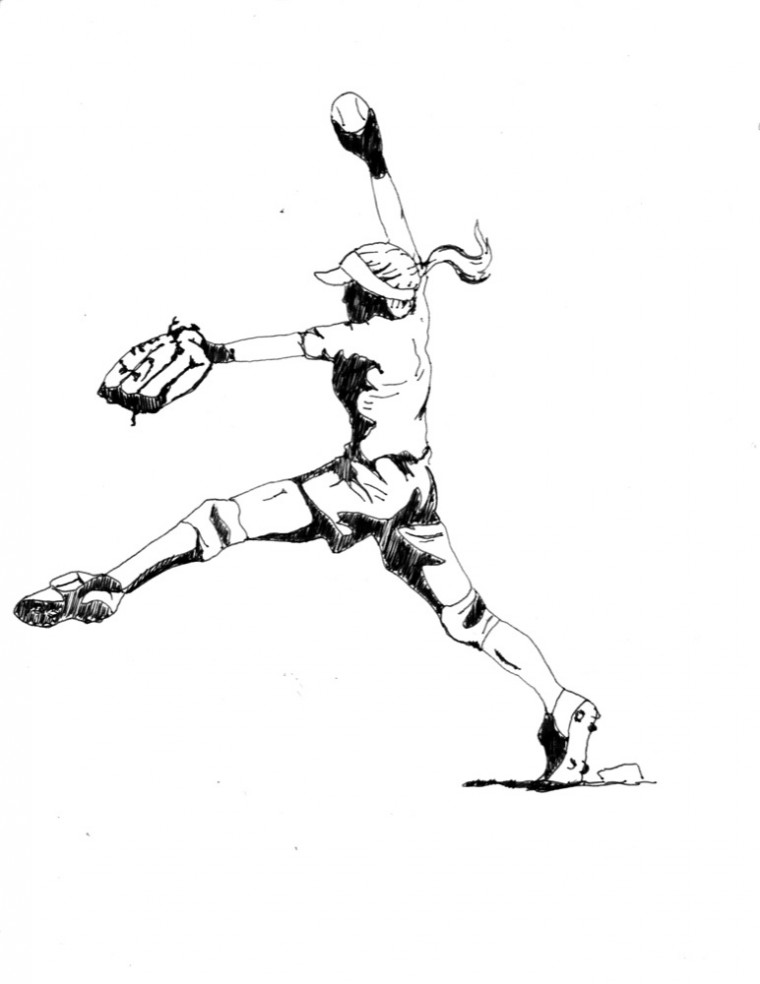

Laura Ancona | Student LifeIf you ever have a free afternoon, head over to the softball field on the west end of the South 40. It doesn’t matter if it’s cold or windy or a little wet—suck it up because you’re going to witness something neat. With any luck, you’ll see her, Annie Pitkin, the righty ace of the Washington University softball team who’s earned her title utilizing a pitch that’s unique to her sport: the rise ball.

Take notes. Hands together, right foot on the rubber, left foot behind, she raises her arms, rocking onto the back of her right heel. The next couple of moments are a flurry of limbs, leather and dirt. Her hands come apart, swinging back past her body at high speed—half like a pendulum and half like a bowstring being drawn. At its apex, her right arm—the one with the ball—is perfectly straight, just about perpendicular to her shoulder. The rest of her body, at this point, looks like a runner in mid-sprint. Her right leg, which was back on its heel at first, is now planted first, with its knee bent, ready to spring. Her left leg is straight back behind her, and her torso is bent at a 45-degree angle to accommodate the torque in her arm. Just before you think her arm is going to pop off and fly away, it comes straight back through where it came. She doesn’t release the ball on the downswing. Nope. Her arm comes through, tracing a circle, while she leaps off the rubber with her right foot, making sure to drag the toe through the dirt of the mound. If she doesn’t, it is an invalid pitch. Her left leg flies low, just above the ground, landing just inside the white circle that loops around the flat mound—about 37 feet from the batter. Her hips fire through, and her hand, now hurtling through the bottom half of the circle, releases the ball just behind her trailing leg with any one of three different grips paired with three different snaps of the wrist. The whole motion from rock to release takes just over a second.

But, when Pitkin lets go of the ball, physics takes over. The Magnus effect, a quirk of aerodynamics, applies a force to the pitch. The law states that any spinning round object (like, maybe, a softball…)will create pockets of low and high pressure. That object is then pushed from the area of high pressure to low pressure. On a rise ball, Pitkin gives the ball as much backspin as possible, putting the pocket of low pressure above the ball, causing it to rise. The ideal version begins at the mid-thigh and ends up at the chest. Ball moves up, batters swing and miss and Pitkin earns conference player of the year.

“It definitely makes a lot of people look dumb when they swing at [her pitch],” sophomore third baseman Hera Tang said.

But how does she throw such a baffling pitch? She splits her pointer and ring fingers parallel along a pair of seams. Her thumb grips the ball below on another seam. As her hand comes through, she leads with her pinky—then she snaps her wrist clockwise— “like you’re turning a doorknob,” she says. You are not trying to open this doorknob quietly; you have to try and tear its screws off. The more spin you give the softball, the greater the Magnus effect and the greater the rise.

A crucial part of the pitch is when Pitkin distributes her weight on release. Unlike a baseball pitcher, who releases from basically the same point and derives motion just from the spin he can put on the ball, softball pitchers vary their balance for different effects. On Pitkin’s rise ball, her weight is back, near her back leg, giving her an angle for the ball to travel up.

And it comes in fast. Although she doesn’t like the radar gun—it makes her tense up, she said—she’s hit as high as 66 mph. She probably sits closer to 60 mph, usually. Although this may not seem too fast compared to the MLB, where guys regularly pump 94-mile-an-hour heat, remember that Pitkin’s pitching from 43 feet away from home plate. Do the math, and a softball batter has the same reaction time for her as a member of the St. Louis Cardinals throwing 93 mph—about 0.45 seconds. Pitkin is currently the NCAA Division III active leader in career strikeouts with 698, with her pitch that defies gravity.

“My rise ball is my bread and butter pitch,” Pitkin said. “That’s what I throw when I’m down in the count; I can throw it for a strike, and I can throw it for a ball and get them to chase.”

The rise ball defies logic, but it is still hittable if you know it’s coming. That’s why Pitkin has two more pitches in her arsenal: a drop ball and a changeup.

Clik here to view.

Laura Ancona | Student Life

Laura Ancona | Student Life“They’re completely opposite pitchers, which is what kind of makes them so good back-to-back against the same team,” junior left fielder Hannah Mehrle said.

With a changeup, Pitkin holds the ball like a drop ball, except she tucks her pointer finger into the area surrounded by the big u-bend in the seams. Between the two extremes, her weight distribution is neutral. The release is what’s really funky. As her arm swings through, she leads with the back of her hand and flips up, kind of like she’s flipping a yo-yo out. The idea is that it travels straight like a regular fastball but comes in much slower and forces the batter out in front. Ideally, a changeup finishes at the batter’s knees or lower. God forbid you let one hang, it could become a 50 mph pinata.

All three combine to mess with the vision of the hitter.

“It’s really hard as a hitter to change planes,” Pitkin said. “If you have a rise ball and a drop ball and a pitch coming in on a flat plane…you’ve got three different planes you’re trying to hit with one bat.”

But one person Pitkin probably isn’t going to fool is Mehrle. Mehrle entered the weekend leading the team in all three major slash categories 0.518/0.831/0.583. The middle stat is her slugging percentage, and if the season were to have ended last Friday, she would place third all-time in major league baseball behind Barry Bonds and Babe Ruth.

Mehrle spent nine years as a pitcher before coming to Wash. U.—and now she can pick up on all the little tip-offs, like a torqued wrist, a difference in stride length. She fancies herself as a good rise ball hitter, and occasionally, she’ll step in against Pitkin for practice. It’s usually a 50/50 battle.

“Sometimes I do well, sometimes [Pitkin] does well,” Mehrle said. “ It depends on the day.”

Her advice for hitting the rise ball is pretty simple.

“You just have to be able to get your hands on top of the ball and hit the ball down, instead of hitting the ball up.”

The big secret though? The rise ball doesn’t actually rise.

Although pitchers and batters will swear on their life that this isn’t the case, in reality the Magnus effect doesn’t have a big enough impact to actually make the ball defy gravity. Instead, it only allows the ball to drop considerably less than a player would expect. Your instincts tell you that the ball is supposed to drop 12 inches—it drops three. Your brain thinks the softball must not be tethered to this earth.

But Pitkin and others shouldn’t care if their best pitch is just smoke and mirrors. Pitching is about deception, and if your pitch can make rookie batters rub their eyes in disbelief, it’s probably a safe bet in a 2-2 count.